NNEXT1

The ancient Greek philosophers were pretty much obsessed with the idea of a good life. I find the philosophers right on especially through the positive psychology movement of today. Research has shown that one of the greatest sources of happiness is “flow”, or the experience we get when doing something challenging that we are good at, whatever that may be; it could be writing, playing music, teaching, cooking, or just talking with friends.

I found that creating art and writing get me in touch with a part of me that appears when I’m creating. I compare it to an umpire in baseball brushing off the dirt from home plate. The creative energy and drive exist in me but can be accessed much better if I’m creating. I’m just entering into the world of cooking. A great relaxer.

I call it getting in the flow of the river of the Universe. sweeping away the stuff that covers up that part of me. Well OK here’s some of my art.

The ancient Greek philosophers taught that true happiness and flourishing come from living an ethical, virtuous life dedicated to personal excellence, wisdom, and harmony. Their ideas shape much of modern positive psychology and continue to inspire those seeking purpose and fulfillment.

The Ethics of the Good Life

Ancient philosophers like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle believed virtuous living was the key to genuine happiness—what they called eudaimonia or flourishing. Instead of focusing on material gain or fleeting pleasures, they argued that a fulfilling life is built on inner harmony, personal growth, and doing good. Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle SPA

Socrates: Virtue and Self-Examination

Socrates taught that “the unexamined life is not worth living” and that happiness comes from developing virtues like wisdom, courage, moderation, and justice. He believed that true happiness cannot be found in external possessions but results from the health and harmony of the soul—achieved by practicing self-examination and striving to do what is right.

There is a story that describes Socrates as having a roommate that engaged in daily examination to assess whether Socrates lived up to his best ethical behavior and told the truth, behaved nicely, and was kind in his actions. It turns out that the friend was actually Socrates asking himself if he lived well and lived up to his moral integrity. This introspective approach is the foundation of the Socratic ideal: “the unexamined life is not worth living,”

Socrates saw the pursuit of virtue as inseparable from the pursuit of happiness.

Engaging in thoughtful dialogue and constant questioning refines our understanding of goodness and helps us live well.

Plato: Harmony and the Soul

For Plato, happiness is a lasting state of inner harmony maintained through the cultivation of virtues guided by reason. He described the soul as having three parts - rational, spirited, and appetitive - and believed that happiness arises when reason governs, resulting in balance and justice.

Wisdom and philosophical contemplation help individuals understand their true nature and make decisions that support their inner peace.

Justice is both a personal and societal virtue: a just person (and a just society) is structured harmoniously, allowing happiness to flourish.

Aristotle: Flourishing Through Virtue

Aristotle’s concept of eudaimonia is central to his ethics. He believed happiness is not a fleeting feeling but a lifelong activity: doing and living well through the practice of virtue.

Human beings achieve their highest good by fulfilling their unique potential through rational activity in accordance with virtue.

Virtues like courage, wisdom, moderation, and kindness are developed by habit and wise choices, making happiness a result of continual growth and effort.

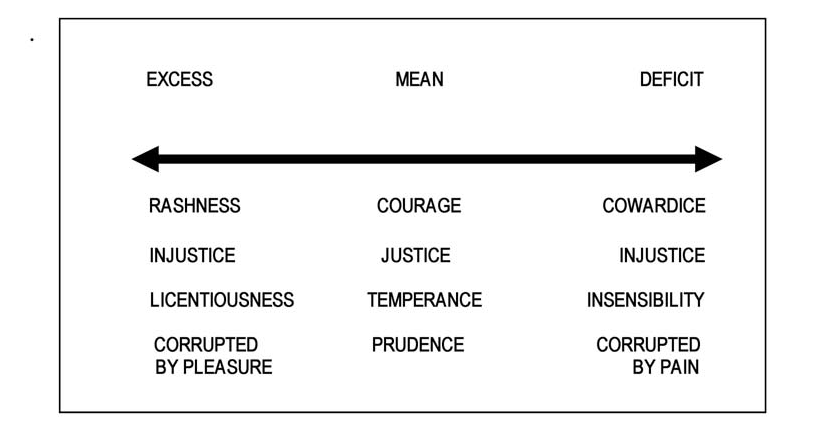

Aristotle’s Middle Path

Aristotle’s Golden Mean is about finding balance in life and actions. He believed that virtue - the best way to live and act - is always in the middle between two extremes:

Too much of a trait (called excess, like recklessness)

Too little of a trait (called deficiency, like cowardice)

Instead of being exactly halfway, the right amount—the “mean”—depends on you and the situation. For example:

With courage: Too little is cowardice, too much is recklessness. Courage itself sits in the middle.

With generosity: Too little is stinginess, too much is wastefulness. The virtue is generosity, in the balanced center.

Aristotle says that acting with virtue means using practical wisdom to choose the right amount for each trait. Virtue is not just average—it’s what helps people flourish and live well.

Wisdom, or prudence, is the capacity to make sensible decisions and judgments based on personal knowledge or experience. It is the ability to recognize, differentiate and choose between right and wrong. It is deemed the most essential of the four virtues. Plato considered wisdom the virtue of reason and believed that being truly virtuous is possible only when one acts on reason. In ancient Greek philosophy, wisdom is regarded as the virtue of rulers, since it enables rulers to take advice and then act prudently, based on their own reasoning. I have gained a lot of wisdom over the long past years.

Courage, or fortitude, is the ability to confront fear, intimidation, danger, difficulty and uncertainty. It is the ability to face a challenge without cowardice. In ancient Greece, courage was regarded as a military virtue, a character trait of soldiers waging war on the battlefield. Both Plato and Aristotle held military excellence in the utmost regard. The soldier was the Greek model for courage and heroism.

As you move through these pages, you’ll find stories, tools, and reflections that shaped my path. I invite you to share your own discoveries, doubts, and triumphs. We can find new ways to grow, reflect, and enrich each other’s journey. Thank you for stopping in and giving yourself permission to reflect and grow.Sign up here to get notified when the content changes.

The journey is better with fellow travelers; I’d be delighted and stoked for any contacts. Even aliens in any definition of that word.

OK, now let’s see some more about me. A hard but good glimpse of what makes sense as to what are ethics and where do they come from. After that we’ll see some info on thinking.

This piece was fused to a temperature of approx. 1650F. Three layers with leaves and spots made with clear dichrotic glass. It’s a dish that is about 4 inches deep, weighs 25 lbs., and has a 2.4 ft diameter. Featured and sold in the Turks and Caicos BWI.oo